ORCHID number: 0000-0002-1195-8842

Email: [email protected]

***

This is a draft entry. The final version will be available in Elgar Encyclopedia of Innovation Management edited by Eriksson, P., Montonen, T., Laine, P-M, & Hannula, A., forthcoming in 2025, Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781035306459

ABSTRACT

This entry explores the new awareness that posthumanist aesthetics brings to the understanding and management of innovation in organizational life. Posthumanist aesthetics emphasizes sensible knowing, aesthetic judging, and the metaphorical and poetic comprehension of innovation. It focuses on the predisposition of the human body to hybridization with other corporealities – nonhuman animals, plant life and nature in general – and with the sociomateriality of organizational artefacts. Posthumanist aesthetics stimulates organizational researchers to investigate the daily metamorphosis of human sensible knowing and aesthetic judging. The entry takes into consideration two cases in particular: medicine and posthumanist design practices. Medicine because human corporeality is highly hybridized due to the digital translation of the human body into data and information which gives it virtual corporeality. Posthumanist design practices because they aim to decentralize the human in the innovation of organizational life.

KEYWORDS

Hybridization of aesthetic feelings, organizational aesthetic research, organizational posthumanist aesthetics, posthumanist aesthetic philosophy, posthumanist design practices.

Outline of the Topic

This entry presents the concept of posthumanist aesthetics in the context of the relationships between organizational theory, aesthetic philosophy, and innovation. Since its origins in the first decades of the eighteenth century, aesthetics has highlighted the corporeality of knowing and acting, as opposed to merely mental and rational knowledge. Aesthetics is based, in fact, on the activation of perceptive-sensorial faculties and on the experiential character of sensitive-aesthetic judgment, as well as on metaphorical and poetic understanding.

Posthumanist aesthetics is in continuity with the philosophical aesthetics of the origins due to the insistence on sensible knowing and aesthetic judgment. It highlights our bodily predisposition of aesthetic feeling to hybridization and metamorphosis. In this way our sentient corporeality connects-in action with the materiality of artefacts and with other corporealities. As happens with our virtual corporeality due to information and telecommunications technologies or with the corporealities of the nonhuman animal, the plant world, and the earth.

The posthumanist conception of aesthetics develops in the broader philosophical and social theory context ranging from Gilles Deleuze’s metaphysical philosophy to Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory, post-feminist epistemology and more-than-human theories. In organization studies and management theory, research on organizational aesthetics has been problematized, refined, and sophisticated by posthumanist aesthetics and provides sensorial knowing, aesthetic judgment, and metaphorical imagination for innovation.

Conceptual Overview and Discussion

Unlike the humanistic aesthetics symbolized by the purity of the aesthetic canons that artistically define the male corporeality of the Vitruvian Man of the Renaissance by Leonardo da Vinci, the posthumanist aesthetics emphasizes the magmatic nature of human corporeality: our flesh is not only sentient but also prefigurative. That is, our flesh refines its welcoming faculties to prepare our carnality for the contaminated experience. Posthumanist aesthetics therefore focuses on our experiential and aesthetic involvement which never remains external. It highlights the somatization that extends our corporeality and the metamorphosis of our corporeality.

Posthumanist aesthetics underlines our bodily predisposition to welcome virtual and non-virtual organizational flux, sociomaterial practice, artefacts, and the otherness of other animal species and nature. These characteristic traits stimulate organizational scholars and students to investigate sociomaterial innovations in organizational life. Posthumanist aesthetics provides a new awareness to the researcher on organizational aesthetics and management philosophy in order to understand and manage innovation in organizational life. Principally, because it invites organizational researchers, philosophers, and ethologists to further explore the everyday metamorphosis of our sensible knowing and aesthetic judging on our hybrid organizational experiences. But, also, because it decentralizes our corporeality in the process of hybridization of our aesthetic experience and problematizes the anthropocentrism of humanist aesthetics.

Art and Innovative Landscapes of Posthumanist Aesthetics

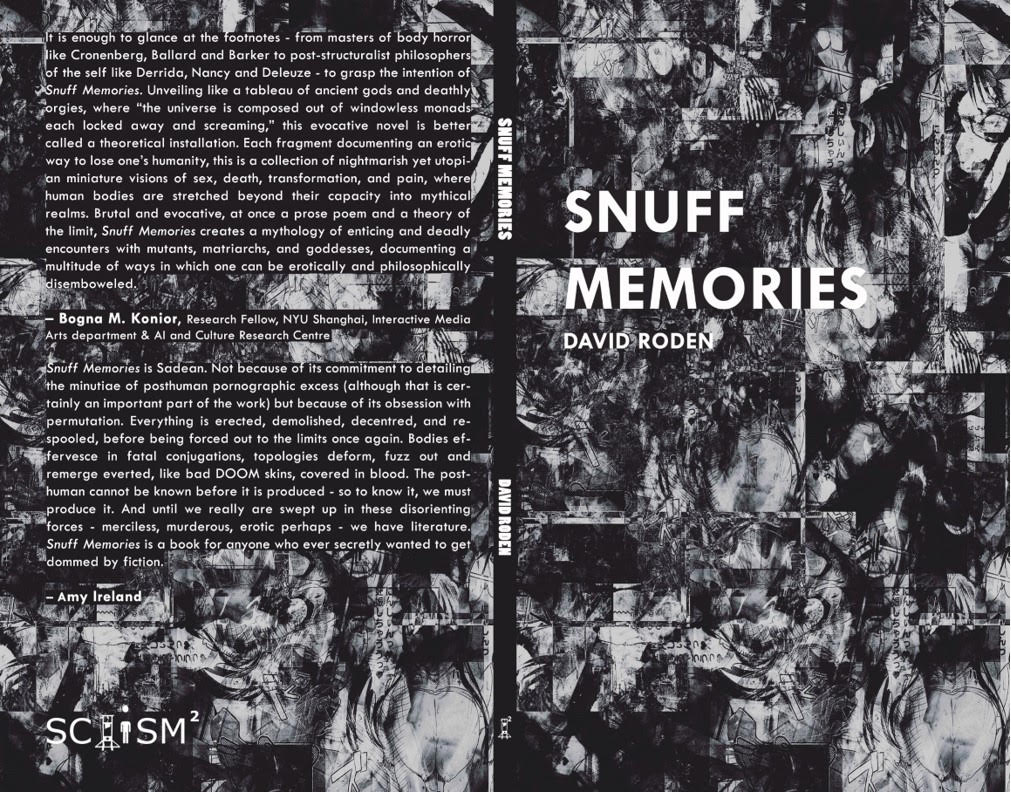

The posthumanist turn in aesthetic philosophy is generally referred to as the Western art scene of the 1990s, and the “Post Human” exhibition curated by Jeffrey Deitch between 1992 and 1993 in Athens, Greece, is believed to have coined the term “posthuman”. The works exhibited at the Athens exhibition were no longer just about redefining art, but also about redefining life. They proposed posthumanist poetics that critically highlighted how, through the combination of biotechnology and computer science, the human was in a process of translation into the posthuman concept of self.

Over the following three decades, posthumanist art was enriched with installations, sculptures, and body artworks such as the performance art of Marina Abramovic. They constituted a corpus of diverse – and dispersed – artistic experiences and works that underlined the desire for increasing freedom from anthropocentric dominion in interaction with other nonhuman animals and with nature in general, as well as with technological innovation. In this regard, French artist ORLAN’s “Carnal Art” manifesto critically conceptualizes how profoundly technical and organizational innovation in information technology is invading human bodies.

The “invaded corporeality” combined with “replicated corporeality”, that is, with the robot that increasingly resembles us. The latter constituted one of the main posthumanist themes and characterized much art, from fantasy and science fiction literature to cinematographic works, to animated films with computer-generated avatars, to immersive interactive experiences in museums based on augmented reality. As well as, more recently, the recording of a Beatles song.

In fact, for the Beatles song “Now And Then”, artificial intelligence was used to lift John Lennon's voice from the original cassette recorded nearly fifty years ago and learn what Lennon’s guitar sounded like. The sounds of Lennon’s voice and his guitar were manipulated, programmed, re-designed, and re-created for this song. This shows the process of decentralization of the human in the recording of John Lennon’s voice and guitar. However, this is only technical freedom from anthropocentric dominion. Because paradoxically – and aesthetically – we recognize Lennon’s singing and playing in the song. That is, we acknowledge it symbolically and celebrate it both culturally and economically.

Listening to “Now And Then”, we may feel surprised and delighted. Or, conversely, we might experience feelings of discomfort and make aesthetic judgments such as macabre and grotesque when we remember that John Lennon was murdered several decades ago. In any case, our aesthetic sense of hearing does not tell us that Lennon’s singing and playing are a successful combination of a recorded cassette and artificial intelligence work. Thus, to what extent can we be confident in our aesthetic judgment and sensible knowing? This interrogative resonates as a classic regarding aesthetic understanding and goes back to the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle and the poetry of Homer. It shows that classical aesthetic dilemmas can remain crucial to posthumanist aesthetics. Even when we feel involved in the materialization of an apparently “impossible” song and in the innovation capacity of information technology and biotechnology which – together with the inventiveness of managerial innovation – make it happen.

I will further illustrate this innovative panorama that posthumanist aesthetics highlights in the next section by discussing the imaginary aesthetic experience stimulated by the desire to enjoy a regional culinary specialty.

Posthumanist Aesthetics and Hybrid Organizational Experience

Let’s consider the case in which we are in Siena as a visiting professor and wish to immerse ourselves in the cultures, tastes, and atmospheres of its gastronomic traditions. Imagine the sound of the voice of a Sienese colleague telling us something like “You can’t leave Siena without tasting pici with wild boar!” Our imagination is stimulated to fantasize about the ordinary aesthetic pleasure of the sensory experience of savouring this Sienese culinary specialty. The aesthetic experiential flow has begun in our corporeality and our flesh is preparing to welcome the pici with wild boar that are not yet in front of us.

To satisfy our fantasy, our desire is, first, to visualize this culinary specialty, to know where it is reputed to be specially cooked, and if we like the look of the restaurant or trattoria. Thus, we place ourselves in the virtual worlds of information systems and telecommunications technologies. In this immaterial world, we exchange data and information relating to our aesthetic desires and choices with the organizational worlds of the Sienese catering or city tourism promotion. That is, we immerse our digitalized aesthetic preferences in the variegated virtual world of different organizational aesthetics, according to the continuously updated innovations of software program applications and the hardware capabilities of the smartphone, as well as in the Sienese computerization of telecommunication systems.

Posthumanist aesthetics explores this metamorphosis of human aesthetic feeling and makes us aware of the paradoxes of our sensible knowing. For instance, something like what we noticed above concerning the Beatles song happens with the image of the pici with wild boar that appears on the smartphone screen. Our sense of sight welcomes it as if it were a photograph. While this image is not – technically and organizationally – a photograph, but a stream of pixels that appears at our request and disappears when we turn it off. We look at the pixels and see a photograph; we perceive the flow of ephemeral electronic signals, and we acknowledge it as if it were a single permanent photograph. Furthermore, the image shown on the smartphone screen may have been realized using artificial intelligence. That is, it could have been produced inductively through virtually stored data relating to the aesthetic preferences of customers and manufacturers regarding this Sienese culinary specialty. In a word, it could have been realized without the sense of sight, without the “photographic gaze”.

In any case, once our pici with wild boar is served, we frame it with our smartphone and send this image documenting the pleasure we feel to family, friends, and social networks. And we also appreciate the beauty of the architectural view of the Torre del Mangia and the Palazzo Pubblico in Piazza del Campo that we glimpse from our table. Then we smell the culinary specialty, explore it with our sense of sight, and we savour it with our sense of taste.

The pici with wild boar smells of homemade pasta seasoned with a ragù that tastes like wild meat. Smell and taste depend on the culinary art of those who cook them, especially since the pici themselves are handmade pasta, and thus they do not always have the same flavour. To form the pici, the strips of dough (wheat flour, salt, and water) are rolled up between the palms (or between the palm and the table), so they neither always have the same length, nor the same thickness, nor do they take the wild boar sauce always in the same way. The ragù is made with game and varies from wild boar to wild boar. The culinary specialty depends on the taste with which the selected raw materials are chosen, on the taste of those who prepare them and of those who cook them, and on the taste of those who – one imagines – will savour them. In a word, the pici with wild boar depends on the dominant aesthetic standards in restaurants and trattorias and, more generally, in the Sienese catering industry. That is, on organizational aesthetic canons which are transmitted by tradition, reinvented in the network of inter-organizational relationships of the Sienese restaurant industry, modified and innovated in the daily relationship with the taste of consumers. Aesthetic canons that are configured in the course of implicit and explicit organizational negotiations of aesthetic preferences.

Sight, smell, touch, and taste are the perceptive-sensorial faculties activated to grasp the gastronomic qualities of this Sienese culinary specialty while hearing tells us the rhythm with which we are savouring it. Does this culinary specialty appeal to our taste buds? Do the flavours of flour, wild meat, olive oil, garlic, and tomato scented with laurel and rosemary respond to the characteristic tastes of our socio-gastronomic culture? Because the wild boar ragù sauce, even if modified and lightened to suit today’s tastes, can still be too strong and disgusting. Furthermore, do we feel right eating other living beings who, fortunately for them, live in freedom? Tasting pici with wild boar highlights how the aesthetic is also discrimination and violence. This feeling, however, is not due to an aesthetic judgment, but to an ethical judgment, and shows the intimate link between the aesthetic dimension and the ethical dimension. In any case, to make both the ethical and taste problems disappear, wouldn’t it be better if wild boar meat were “cultured” – that is, produced through the cultivation of wild boar cells “in vitro” – rather than wild?

Posthumanist aesthetics investigates the paradoxes and metamorphoses of our sensible and perceptive faculties and of our sensitive-aesthetic judgment in the hybridized sociomaterial landscapes in which we immerse our hybridized corporeality. As fingers do with honey. While the honey allows itself to be grasped by the fingers, the fingers remain entangled in the honey which creeps stickily between them, observes the phenomenological philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, inspired by the reflections of another French philosopher, the existentialist Sartre. The posthumanist aesthetic understanding of organizational life shows that, like honey, what we seek to understand aesthetically by extending the capacity of our sensible knowing and manage at the organizational level is autonomously in action. It is elusive, mixed up of completely diverse corporeality and matter, and in a continuous flux that confuses our sensorial faculties and our aesthetic judging.

Application: Posthumanist Aesthetic Awareness in Medicine and Design Practice

Posthumanist aesthetics refines the aesthetic understanding of organizational life. It provides organizational scholars, consultants, and managers with a new awareness for comprehending and managing innovation in organizational worlds. In medicine, for example, just to indicate a fundamental area of study. As well as in design practices aimed at freeing ourselves from anthropocentric organizational culture and symbolism.

Posthumanist Aesthetics and Medicine. Our corporeality in medicine is highly hybridized. It is indeed made of flesh, of perceptive faculties and of sensorial judgment. But it is also made of the virtual translation of our body into digital materiality. That is, in the set of data and information that give virtual corporeality to our body, and make it configurable by algorithms and modelable through standard procedures. In the arts, more than a century ago, Giorgio de Chirico painted his famous mannequins to free Mediterranean metaphysical art from anthropomorphism by translating human corporeality into a thing. That is, in an active matter that follows its own paths.

The immediacy of the bodily experience that the doctor can have of us is hybridized by the digitalized body that the doctor can learn through data and information concerning our body. S/he can feel our heart beating, our blood circulating, our breathing rhythmizing our body while the data collected through CAT scans, X-rays, laboratory analyses, and spirometry tests convey our corporeality in its quantitative, digitized, virtually comparable model. That is, in its being a “thing”. This also applies to the medical care for nonhuman animals and plant life.

Posthumanist Aesthetics in Design Practices. Posthumanist aesthetics can inspire design practices that acknowledge intelligent systems as partners of humans. Drawing from the writings of Tim Ingold, among others, Laura Forlano emphasizes that posthuman-centered design practices can accommodate revolutionary change due to the growing power and diffusion of information technology. Such practices can also further explore post-anthropocentrism regarding artefacts of daily use, as well as trees, rocks, and nonhuman animals. That is, acknowledging in design practice that the human world is in interspecies connections and in a relational continuum with the natural, geographical, and ecological world, as Seray Ergene and Marta Calás illustrate. Indeed, although artefacts and artificial intelligence are predominant partners in design practices, it is also important to bring to light the biological and ecological dimensions of aesthetic experience in design practices. Starting from giving due consideration to sensible knowing and acting of nonhuman animals, underline Julie Labatut, Iain Munro and John Desmond.

More generally, posthumanist feminist aesthetic understanding can be taken into consideration when designing the sociomateriality of organizational practices, points out Silvia Gherardi. This thesis resonates in the arts with the feminist exploration of the body introduced by the performances of the Sixties and Seventies and with the radical re-elaboration of the self in Cyberfeminism and bioart, as Francesca Ferrando argues. And which must also be extended to art curatorial practices, Rosi Braidotti remarks, to challenge both the anthropocentric assumptions of museum curatorial practices and the Eurocentric humanistic universalism that characterizes them.

Critical summary

Posthumanist aesthetics refines and sophisticates the aesthetic understanding of innovation in organizational life. It focuses, in fact, on the sensitive and experiential dimension of hybridized fluxes of organizational interaction. Hybridization is due to the intertwined relationships between the continuous metamorphosis of human corporeality and the continuous innovation in bioinformatics technology, as well as the metamorphosis that occurs amongst other animal species and nature in general.

Posthumanist aesthetics has been explored in organization studies principally in recent years and in a fragmented way. Indeed, organizational theories and management studies have mainly given prominence to the ethical dimension of posthumanism, as well as to the post-feminist epistemologies that have explored it and, also, to posthumanist ecological and socio-political issues. Organizational theories and management studies have thus reflected philosophical research and study, in which posthumanist aesthetics are rarely researched and theorized thoroughly as the ethologist and philosopher Roberto Marchesini does with his book published in Italian in 2019.

In particular, in the literature on organizational aesthetics, the theoretical side of posthumanist aesthetics has been privileged, leaving the empirical investigation of the posthumanist aesthetics of organizational innovation in the shadows. Despite these limitations, however, posthumanist aesthetics inspires and stimulates the study of relevant aspects of innovation in organizational life. This is because it focuses on knowing and acting that are based on pleasure or its opposite, on languor or disgust, on the shiver on the skin and the grip in the stomach. That is, it focuses on sensible knowing, aesthetic judging, and metaphorical and poetic understanding of organizational innovation.

Further readings

Braidotti, R. (2019). Posthuman Knowledge. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Ergene, S., & Calás, M. B. (2023). Becoming Naturecultural: Rethinking sustainability for a more-than-human world. Organization Studies, 44 (12), 1961-1986.

Ferrando, F. (2016). A feminist genealogy of posthuman aesthetics in the visual arts. Palgrave Communications 2 (article N. 16011). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.11.

Forlano, L. (2017). Posthumanism and design. She Ji, The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 3 (1), 16-29.

Donger, S., Shepherd S., & ORLAN (Eds.) (2010). ORLAN: A hybrid body of artworks. New York, NY and London, UK: Routledge.

Gherardi, S. (2022). A Posthumanist Epistemology of Practice. In Neesham, C. (eds), Handbook of Philosophy of Management. Handbooks in Philosophy. Cham: Springer, pp. 99-120.

Labatut, J., Munro, I., & Desmond, J. (2016). Animals and organizations. Organization, 23 (3), 315–329.

Strati, A. (2019). Organizational theory and aesthetic philosophies. New York, NY and London, UK: Routledge.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed